In January 1931, during the Great Depression, mutton was literally the bone of contention in Adelaide. More than 1000 unemployed men and their families assembled at Port Adelaide to march to the city in protest at the replacement of beef with mutton on their ration tickets. Mutton was thought to be full of bone and inferior to ‘good red beef’. The Unemployed Workers Movement, other unions and other labour organisations led the march. Wally Bourne, one of the demonstrators, recalled that Port traders gave the marchers an enthusiastic send off by giving them fruit, pies and pasties: ‘So it was not just the unemployed, or not just the Communist Party, it was Port Adelaide on the march’.

Approaching the city

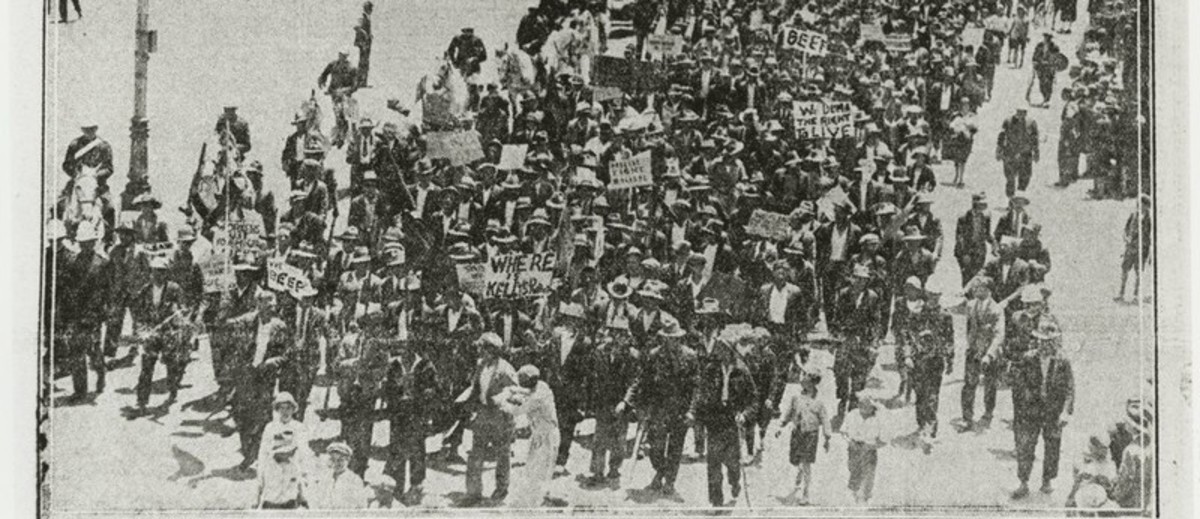

As the marchers approached the Southwark Hotel on Port Road near the city, they were joined by about 1000 unemployed Adelaide men. The women and children had marched in solidarity but most of them now left the march as it continued under a strong escort of mounted, motorcycle and foot police. The marchers carried banners that read ‘We want beef’, ‘Down with imperialism’ and ‘Hands off China’, and waved red flags and union placards.

The Advertiser newspaper reported that the demonstrators progressed along North Terrace ‘in an orderly fashion’ and turned into King William Street where they held up traffic. The men finally congregated at the front of the Treasury Building, where a deputation of six was assembled to discuss ration tickets with the government. In front of the building was a contingent of uniformed constables. Superintendent McGrath, who was in charge of the police operation, was spoken to by the leaders, who demanded that they be allowed to interview Premier Lionel Hill, the leader of the Labor Party. Unknown to the demonstrators, behind the Treasury doors was a squad of police in readiness.

A cruel disappointment

Wally Bourne recalled what happened when the two big doors of the Treasury opened:

instead of the minister being there to greet us, there was the police force in all its glory, and behind us, in the half hour we’d been waiting there … was the mounted police. In other words we were completely ambushed, and that was the actual riot, then when the police came out swinging their batons, they were horribly surprised to see that the unemployed workers were also swinging their batons and taking the blows of their batons on their arms. Now that battle was actually a battle, and it raged right across the square.

The News report stated:

blows were struck, and in a moment mounted troopers with batons drawn, and plainclothes constables were battling with an infuriated crowd. Several men dropped to the ground with blood streaming from wounds in the head, and hats and coats and the placards which had been carried by the demonstrators were strewn in disorder over the footpath and roadway.

Aftermath

After about 20 minutes of intense fighting, the police charged with more mounted and motorcycle officers and the crowd began to disperse. Demonstrators injured in the attack were picked up by their comrades and taken to Victoria Square to be treated, and some were sent to the Royal Adelaide Hospital. Several of the police had sustained significant blows from missiles and sticks, and some demonstrators had been trampled in the crush: 17 people needed hospitalisation, including ten policemen. Twelve arrests were made, six of the men being members of the Communist Party.

That week there were other demonstrations and protests, particularly against the use of force by the police and against local butchers who were refusing to give beef rations to the unemployed. The next week a large group of unemployed men presented a list of demands to Chief Secretary Stan Whitford. These included the unconditional release of all persons arrested in the riot, the restoration of beef to the ration list and free passes on trams and trains. Most of these demands were not met, although beef did eventually return to the ration tickets.

Long-term effects

The effects of the Beef Riot were felt in South Australia for a long time. The militancy of the unemployed was officially discouraged as much as possible from this time onwards in Adelaide. Police Commissioner Brigadier Leane informed the government that the police would in future disperse all such demonstrations immediately. This impacted on unions and the Communist Party. The government set up relief camps for single unemployed Adelaide men, especially those being housed in the Exhibition Building on North Terrace. That site was closed down in mid November 1931. While the relief camps were set up specifically in isolated country to prevent further mass protests in the city, the camps served only a very limited number of men.

Premier Hill and the other five members of his ministry were casualties of a different kind: in August 1931 they were expelled from the Labor Party on the grounds that they had become alienated from the labour movement by their behaviour and attitude towards the unemployed.

Advertiser, 10 January 1931, ‘Story of scene at Treasury Building’, p9

Border Watch, 13 January 1931,’ The Adelaide riot’, p3

Broomhill, Ray, ‘The social history of Adelaide during the Depression’, typescript, 197?

Broomhill, Ray, Unemployed workers: A social history of the great depression in Adelaide (Brisbane: University of Queensland Press, 1978)

News, 15 January 1931, ‘Unemployed demands’, p15

News, 9 January 1931, ‘Riot in Adelaide streets after unemployed parade’, p1

State Library of South Australia, OH24/18, Interview with Wally Bourne, 1978

Add your comment