Geographic Origins

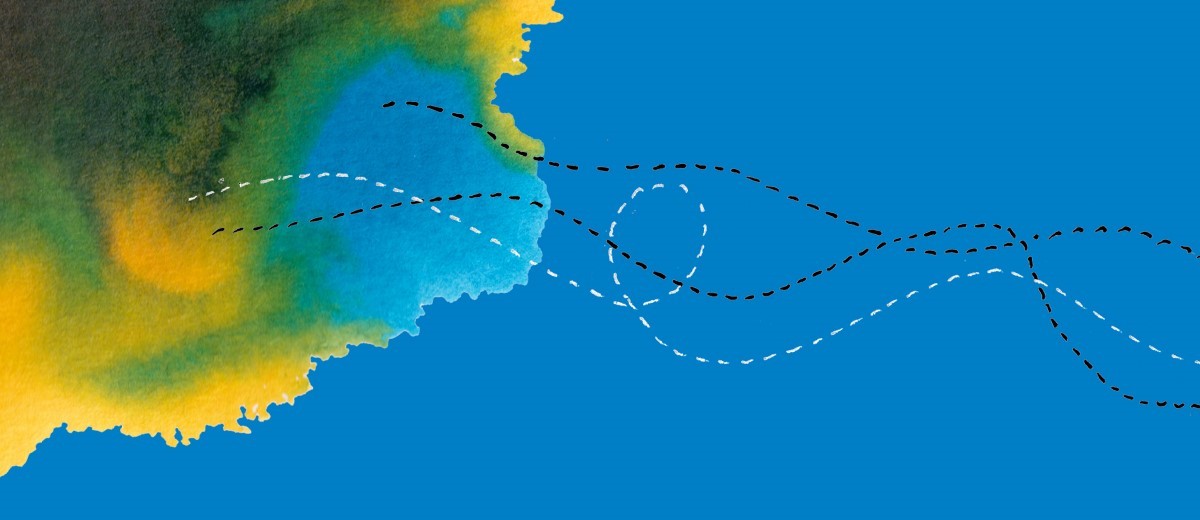

Cornwall is a county in the south-western region of Britain. It has shores on the Irish Sea and the English Channel.

History of Immigration and Settlement

Cornish immigration to South Australia has long been associated with mining, but early Cornish settlers arrived before the first discovery of mineral deposits at Glen Osmond in 1841. Many Cornish Methodists and liberals had been attracted to South Australia by its non-penal, utilitarian basis and strongly non-conformist ideals. Most of these early settlers came as labourers and found work in a variety of jobs, including digging wells. The miners among them readily adapted to this work.

The offer of free passage from England to South Australia before the discovery of minerals in 1841 was well received by Cornish immigrants. Some 941 Cornish families applied for these passages and accounted for 10 per cent of all applications lodged in the United Kingdom. Fifteen per cent of all assisted passages to South Australia between 1836 and 1841 were from Cornwall. The number of Cornish immigrants sent to South Australia was disproportionately high considering Cornwall’s relatively small population.

The discovery of the rich silver-lead lode at Glen Osmond resulted in several mines being opened, including Wheal Gawler and Wheal Watkins. Wheal is a Cornish word for a single shaft or mine. Many Cornish men who had previously been employed in other occupations in South Australia took on work as miners. The declining fortunes of Cornish mines and the corresponding rise of mining in South Australia after 1841 directly influenced the number of Cornish immigrants who came to South Australia.

The discovery of copper in 1843 at Kapunda and further discoveries at Burra in 1845 provided great opportunities for Cornish miners, who were highly sought after. Those in the colony employed in other pursuits abandoned their jobs to take up mining. The colony’s immigration agents set up permanent bases in several Cornish towns to aid the flow of miners to South Australia. Cornish people had no peers as hard rock miners. It was this knowledge and skill that led to their domination of the South Australian mines. In line with Cornish tradition an experienced miner, Thomas Roberts, became the first mine captain, manager, of the Burra Burra mine in 1846.

The Cornish community’s numerical strength and economic importance was reflected in the Cornwall Devon Society, which was founded in South Australia in 1850. The society acted as a political pressure group for the colony’s considerable number of Cornish immigrants. Between June 1850 and May 1851, one in seven of all immigrants to South Australia was Cornish.

The Victorian gold rushes of the 1850s temporarily altered this pattern. Cornish miners in South Australia and those leaving Cornwall were lured to the Victorian fields by the prospect of gold. The lack of miners caused the temporary closure of many of South Australia’s smaller mines. Mining companies were quick to rectify this situation by specially recruiting their own miners from Cornwall. During 1854 and 1855 1,600 Cornish miners and their families were sent to South Australia. By 1861 this number had risen to 5,135, 10.5 per cent of all government sponsored immigrants. Of the 2,117 male Cornish immigrants who came to South Australia at this time, 84.9 per cent were miners.

The discovery of copper on Yorke Peninsula between 1859 and 1861 marked the beginning of a new age in South Australian mining and prompted further Cornish immigration. Cornwall’s economic position had continued to decline, while South Australia was entering a new phase of development. Between 1862 and 1870, 3,651 Cornish people emigrated. This accounted for 27.5 per cent of South Australia’s new arrivals. For the earlier period of 1863 and 1864, the Cornish accounted for as many as 42.5 per cent of all South Australian immigrants.

South Australia’s ‘Copper Triangle’ of Wallaroo, Moonta and Kadina became known as ‘Little Cornwall’. It overtook the Kapunda and Burra mines as the leading producers of copper and as the main destination for Cornish immigrants. When the Burra and Kapunda mines ceased production in 1877 and 1878 respectively, many miners turned to farming and contributed to the expansion of the northern agricultural frontier.

On Yorke Peninsula the demand for Cornish miners and mine captains continued. In 1882 the last significant recruiting drive was carried out in Cornwall. This drive was successful in attracting 408 Cornish immigrants. Despite such Government migration schemes being abandoned in 1886 the concentration of large numbers of Cornish miners in the northern area of Yorke Peninsula resulted in the Cornish community remaining a readily identifiable group until the mid-1920s.

Cornish immigrants have continued to come to South Australia since the Second World War, but their numbers have been comparatively small and they have been rapidly absorbed into the general population. Their immigration has not resulted in the establishment of identifiable Cornish communities in South Australia.

Cultural Traditions

The Cornish immigrants of the nineteenth century maintained numerous cultural traditions in South Australia. The Cornish settlements of northern Yorke Peninsula continued to celebrate the northern hemisphere’s Midsummer’s Eve with bonfires and fireworks, and to conduct funerals in the elaborate tradition of tolling bells and long processions behind the casket. Many miners guarded themselves against cave-ins and other dangers of the mine by observing age-old customs. They would be careful not to turn to face their house once they had left for a shift, refrained from whistling underground, and befriended the knockers, the creatures they believed to inhabit the mines, by leaving remnants of Cornish pasties for them. They believed that it was unlucky to burn eggshells, sweep dust from a house or put shoes on a table. Some of these traditions have been passed on to the descendants of Cornish immigrants.

Community Activities

Before the discovery of minerals, the Cornish had made their presence felt through the three branches of Methodism in South Australia: the Primitive Methodist, Bible Christian and Wesleyan Churches. Many Cornish immigrants had been attracted to South Australia by the religious freedom that it offered. Methodism flourished because it was the only denomination to rely on lay preachers rather than ordained ministers. Methodism held a prominent place in the districts that Cornish people settled throughout the 1840s. The impact of these Cornish immigrants on mining settlements was profound. In many instances, what had been a ‘raw and riotous mining camp’ became, with the help of Cornish Methodist miners, a Christian and generally law-abiding community.

Cornish immigrants during this period accounted for 8% of total immigrant numbers. Of the 100 Methodist clergymen who came to South Australia during the period 1849 to 1930, over one third were from either Cornwall or Devon. The impact of the Cornish in South Australian religious life was relatively strong throughout the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth century.

The Cornish, notably the Boucaut, Rounsevell, Bonython, Rowe and Verran families, also made a clear impact in other social spheres of South Australian life. The numerical strength of the Cornish in mining towns was obvious in the local newspapers, which published articles and letters in a Cornish dialect on special occasions such as the Duke of Cornwall’s birthday. Church events and special services, including the Sunday School Anniversary and Picnic, were an integral part of the Cornish lifestyle in the upper Yorke Peninsula. Other special events to receive newspaper coverage in a Cornish dialect included the Feast day of Piran, the patron saint of miners, and wrestling matches, a favourite Cornish sport. In Adelaide, the Brecknock Arms hotel was run by a Cornish immigrant and was a major venue for Cornish wrestling. It held 2,000 people. Another sport introduced from Cornwall was cockfighting, also very popular among the Welsh. The Cornwall and Devon Society, though short-lived because of the many miners who sought wealth in the Victorian goldfields, aimed to encourage Cornish immigration to South Australia by watching over the interests of Devon and Cornish colonists, and promoting harmony among them.

The predominance of Cornish immigrants in mining areas meant that they had a profound influence on the way mining was undertaken. Mines were often owned by English capitalists, but operated by Cornish captains and miners. The work practices of miners closely mirrored those of their counterparts at home. Mining equipment such as engines, pumps and crucibles was initially imported to South Australia direct from Cornwall.

A sense of Cornish identity among South Australian communities remained strong even after the last group of assisted migrants arrived in 1886. The amalgamation of the Wallaroo and Moonta mines in 1890 and the union of various Methodist denominations in 1900 served to preserve Cornish identity. Both were important vehicles of Cornish culture.

After the turn of the century many of the South Australian communities that had been proudly Cornish were progressively absorbed into mainstream society or moved to other mining areas in New South Wales and Queensland. The Cornish radical tradition continued to play a part in the growth of the labour movement until the collapse of the South Australian mining industry in 1923. Moonta born John Verran was Labor Premier of South Australia between 1910-1912.

The state of South Australia owes a great deal to the philanthropy of John Langdon Bonython. Some of his more notable philanthropic acts relate to the completion of Parliament House and Bonython Hall in 1934, the University of Adelaide Law School and the South Australian School of Mines.

The Cornish Association of South Australia has remained active since its foundation in 1890. It is a focal point for newly arrived Cornish people, as well as those of Cornish descent. The association also co-operates with the Kernewek Lowender Organisation, which holds the biennial Cornish Festival on Yorke Peninsula.

Organisations and Media

- Cornish Association of South Australia

- Kernewek Lowender Incorporated

Statistics

In the 1986 census the Cornish were incorporated with people of Breton, Celtic and Manx descent. 2,436 people were included in this group.

Details about Cornish South Australians were not included in the 1991, 1996, 2001, 2006, 2011 or 2016 census counts.

Auhl, I, The Monster Mine, (Adelaide: Investigator Press 1986)

Faull, JF, Cornish Heritage: A Miner’s Story, (Adelaide: 1980)

Faull, JF, The Cornish in Australia, (Melbourne: AE Press, 1983)

Hancock, DC and Paterson, RM, Cousin Jacks and Jennys (Cornish Association of South Australia, 1995)

Hilliard, D and Hunt, A, ‘Religion’, in The Flinders History of South Australia: Social History, ed. Eric Richards (Adelaide: Wakefield Press, 1986)

Hunt, AD, This Side of Heaven, (Adelaide: Lutheran Publishing House, 1985)

Jupp, J (ed.), The Australian People: An Encyclopedia of the Nation, Its People and Their Origins, Second Edition, (Cambridge University Press, 2001).

Paterson, RM, Thank You Walter Watson Hughes (Adelaide: Gould Publishing, 1993)

Paterson, RM, ‘The Cornish Heritage on Northern Yorke Peninsular: The Cousin Jenny Contribution’, unpublished paper.

Payton, PJ, The Cornish Miner in Australia, (Fowey: Dyllanson, 1984)

Payton, PJ, Pictorial History of Australia’s Little Cornwall (Adelaide: Rigby, 1978)

Payton, PJ, Cornwall (Fowey: Alexander Associates, 1996)

Payton, PJ, The Cornish Overseas (Fowey: Alexander Associates, 1999)

Pryor, O, Australia’s Little Cornwall, (Adelaide: Rigby, 1969)

Yelland, EM (ed), Colonists, Copper and Corn (Adelaide: Yelland, 1983)

Add your comment