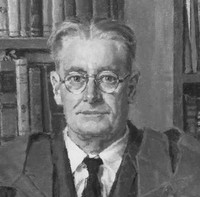

Howard Walter Florey was born in Adelaide, South Australia, on 24th September 1898, the son of boot manufacturer Joseph Florey and his second wife, Bertha Mary (née Wadham). He was educated at St. Peter’s College where a remarkable teacher, ‘Sneaker’ Thompson, fostered his interest in chemistry. The boy shone, winning prizes and scholarships, and playing cricket, tennis and football for his school. He graduated in medicine at the University of Adelaide in 1921 and went as a Rhodes Scholar to Oxford University, where he obtained further degrees. On 19th October 1926 he married a fellow Adelaide graduate, Dr. Ethel Reed. He worked in the United States and England, and in 1935 was appointed Professor of Pathology at Oxford University, a position he held until 1962.

While at Cambridge, Florey had investigated lysozyme, an enzyme with anti-bacterial properties, present in tears and mucus. At Oxford he recruited Ernst Chain, a brilliant German biochemist, to assist in this work. They found that lysozyme killed some bacteria but none that caused fatal diseases. They turned to other naturally occurring anti-bacterial substances, including penicillin which Alexander Fleming had discovered in 1928 but failed to stabilize effectively for human use. Through 1939 Florey and his team concentrated on penicillin and by the following year they had solved the problems of isolating and preserving it that had defeated Fleming. They tested it successfully on mice and then on humans. Americans contributed techniques for its mass production and took out patents, which Florey had refused to do, wishing to give the discovery to all.

Here was the world’s first antibiotic that could counter a wide range of infections, including bacterial pneumonia, septicaemia, meningitis, osteomyelitis and puerperal fever. In Florey’s words, ‘Penicillin is almost completely non-poisonous to animals. Most antiseptics not only kill bacteria, but also kill the white cells. Penicillin does not kill bacteria, but only stops their growth. Then the white blood cells come along and eat them.’

Despite Florey’s resistance, his wife continued her career, doing much of the clinical testing of penicillin on patients at the Radcliffe Infirmary in Oxford.

Hundreds of millions of people have lived longer and healthier lives as a result of Florey’s work. It brought him a rich harvest of honours. He was knighted in 1944, shared the Nobel prize for physiology and medicine with Fleming and Chain in 1945, and was awarded the U.S.A. Medal for Merit in 1947. In 1965 he was created Baron Florey of Adelaide and Marston, and became a member of the Order of Merit. He was also the first Australian president of the Royal Society (1960-65), the pinnacle of British science. He continued to work on antibiotics for a time, then turned to the field of strokes and heart disease. Invited to head the John Curtin School of Medical Research at the Australian National University in Canberra, he declined but visited Australia to open the school in 1957 and became chancellor of the University in 1965.

Florey’s first wife died in 1966 and on 6th June 1967 he married Dr. Margaret Jennings (née Fremantle), his colleague at the Sir William Dunn School of Pathology. By his own account he had not been a dutiful or loving son, his marriage to Ethel was unhappy for both of them and he found it hard to express affection for his children. His brief second marriage was, however, a happy one. He died in England on 21st February 1968 and was cremated. A memorial tablet was placed in St. Nicholas’s parish church at Marston, Oxfordshire, where he lived, and a commemorative stone of South Australian marble was erected in Westminster Abbey. It reads: ‘His vision, leadership and research made penicillin available to mankind.’ A head in bronze by John Dowie is situated in the Prince Henry Gardens on North Terrace, Adelaide.

Macfarlane, R.G., Howard Florey: The making of a great scientist (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979).

Williams, T.I., Howard Florey: Penicillin and after (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984).

Add your comment