The South Australian government involved itself in the labour market from the outset. Edward Gibbon Wakefield’s plan aimed to secure an optimal balance of capital and labour, while assisted migrants who could not find private sector jobs were promised public employment. However, after George Gawler’s public works program bankrupted the colony, Governor George Grey renounced this promise and sharply reduced public investment. By the end of 1841, 14 per cent of the population was on government relief. By applying a work test to public relief, Grey drove the unemployed out of Adelaide to work for outlying farmers and graziers offering very low wages. A draconian Masters and Servants Act 1837 helped keep them there.

Despite these and other troubles, Australia’s first ‘free’ colony did attract, over time, a viable balance of investment and employment. By 1857, 73,363 people had arrived on assisted passages. While the Victorian goldrushes financed a new burst of land sales and a hefty increase of assisted immigration, the 1860 election returned a majority which, for the first time, responded to unemployment by suspending assisted immigration completely. In the years since, immigration, largely assisted, has been an important source of labour. Of overwhelmingly Anglophone origin until the 1950s, net immigration was highest between 1840 and 1860, 1875–85, 1905–25 (excluding the First World War) and 1950–65.

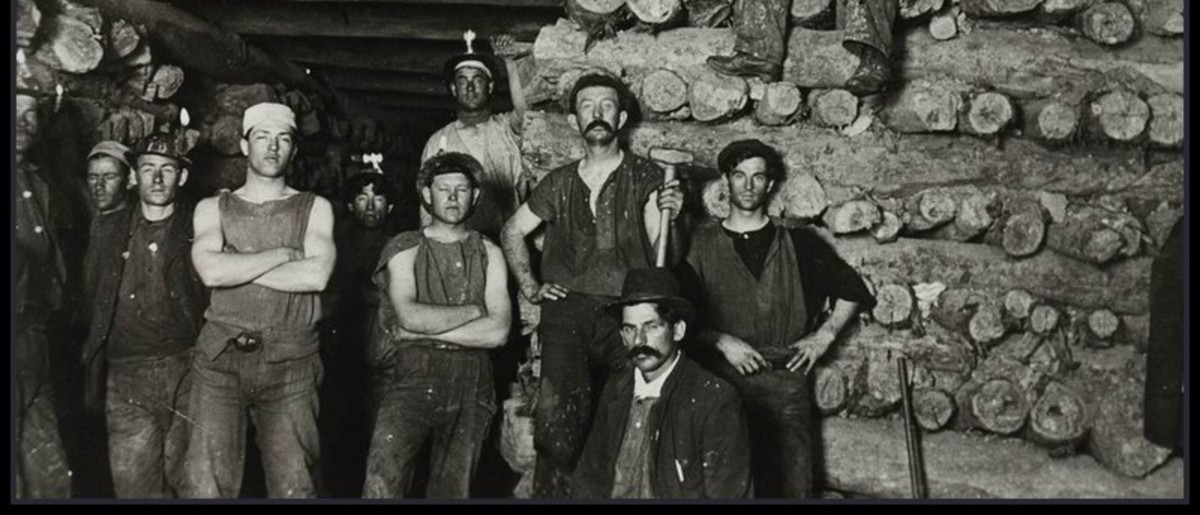

Employment in Mining and Primary Industries

Mining was an early contributor to rural employment. South Australia was the British Empire’s biggest source of copper through much of the nineteenth century, attracting experienced miners, especially from Cornwall. Employment expanded in transport, metalworking, smelting, and the farming, house-building and urban trades that fed and accommodated miners. Employment also benefited from mines elsewhere in Australia, as South Australian firms produced machinery for mines in New South Wales, Western Australia and the Northern Territory, escorted gold from the Victorian fields to mint and export from Adelaide, and transported and smelted ores from Broken Hill. Primary production from mines, pasture, farms and vineyards was employing 43 per cent of the workforce in South Australia in 1871, when the Australian average for the sector was 31 per cent. South Australia also had a bigger proportion of service jobs, 36 per cent against the average of 26. The 21 per cent in construction and manufacturing was less than half the Australian average.

From 1876 mining employment declined as copper orebodies were worked out. The farm–pastoral sector always made use of unpaid family labour, particularly from females. Output growth in the primary sector tended to rely increasingly on capital inputs rather than labour. All sectors were hit by a combination of slump and drought in the 1890s, which sent unemployment soaring to levels barely surpassed in the Great Depression.

Employment in the Twentieth Century

In the new century the development of manufacturing at first rested on federal policy and local entrepreneurs. Advance knowledge of proposed national protection, for example, prompted Holden’s to start making car bodies in Adelaide in 1918. The Great Depression changed things. From 1928 to 1934 inclusive, South Australian unemployment was four to five per cent above the extremely high national average. Hence the state government adopted policies explicitly aimed at boosting employment. Industrial development was planned chiefly by J W Wainwright, led by premiers Richard Butler and Tom Playford, and accelerated by the use of wartime powers during and after the Second World War. State agencies attracted private industrial development, benefiting workers as well as investors. State arbitration tribunals pegged wages to local consumer price indexes. The South Australian Housing Trust provided low-cost public housing close to the new factories, which together with ample public land supplies helped restrain private housing costs and rents. During and after the war there were some direct price controls, especially on items represented in the consumer price index. Directly and indirectly those measures kept South Australian industrial workers’ costs of living and labour costs lower than those in the eastern states. High federal tariffs protected manufacturing during the 30-year post-war boom and South Australia’s proportional share was above the national average. While employment in primary industries declined from 22 to 10.6 per cent of the state’s total, the percentage in manufacturing rose from 15.5 to 27.8 per cent between 1933 and 1966, by which time services employed 54 per cent of the workforce.

Trade unions and compulsory arbitration helped weekly hiring replace daily hiring in most industries by 1939 and progressively reduced typical ‘standard hours’ worked from over 50 per week in 1900 to 38 in the mid 1980s. This trend was then reversed for many. Until the 1980s the workforce was overwhelmingly full-time. Social mores long dictated that, if not required for unpaid ‘home duties’, women should only work before marriage or when widowed. In 1961 they constituted less than a quarter of the workforce. Changing attitudes saw their share rise to 38 per cent in 1981, but still only 45 per cent of working-age females were in the workforce, compared with 77 per cent of males. The female legal minimum wage was barely half that of males until 1950, when it was increased to three-quarters. Movement towards equal pay only began in the 1970s, but even so the occupations in which women were congregated continued to be regarded as lower skilled – and were hence lower paid – than traditionally male jobs.

Rising Unemployment

Full employment ended in the 1970s. Technical change, lower protection and cost-cutting pressures reduced the opportunities and security of employment for many, particularly the least skilled and lowest paid. As manufacturing jobs shrank proportionately back towards the 1933 level, the state’s economy became the mainland’s worst performer. In June 1992 unemployment peaked at 12 per cent. In June 2000, at 8.2, it was 1.6 points above the national average. One effect has been net emigration to other states. Long-term unemployment became a serious concern.

Stagnation of Full-Time Employment

Full-time employment stagnated in the 1990s, in contrast to part-time, casual and contract hiring, particularly in the services sector. Services accounted for 70 per cent of employment in 2000 when part-timers constituted 30 per cent of all employees – although a quarter of them would have liked more work. Most were women who, in total, now constituted 43 per cent of the state’s workforce. Female participation rates rose accordingly; 52 per cent of women over 15 were now in the workforce. The male rate fell to 71 per cent. The combined participation rate reflected the state’s increasing employment problems, sliding well below the national average. Under flexible-time contracts the spread of daily working hours was greatly extended.

In addition to unemployment and underemployment, cost-cutting and downsizing pressures reduced security in many areas of employment. Increasing wage inequality also had its effect. There is evidence of increasing stress and declining work satisfaction for a rising proportion of employees. In a 1995 national survey, more than half of the South Australian employees surveyed reported working harder, under greater stress, less happily, than in previous years.

Morehead, A, Changes at Work: The 1995 Australian Workplace Industrial Relations Survey (Melbourne: Longman, 1997)

Richards, E (ed.), The Flinders History of South Australia: Social History (Adelaide: Wakefield Press, 1986)

Sheridan, K, (ed.), The State as Developer: Public Enterprise in South Australia (Adelaide: Royal Australian Institute of Public Administration in association with Wakefield Press, 1986)

Vamplew, W, ‘South Australians 1836–1986. A statistical sketch’, in G C Sims (ed.), South Australian Yearbook (Adelaide: Australian Bureau of Statistics, South Australian Branch, 1986)

Add your comment