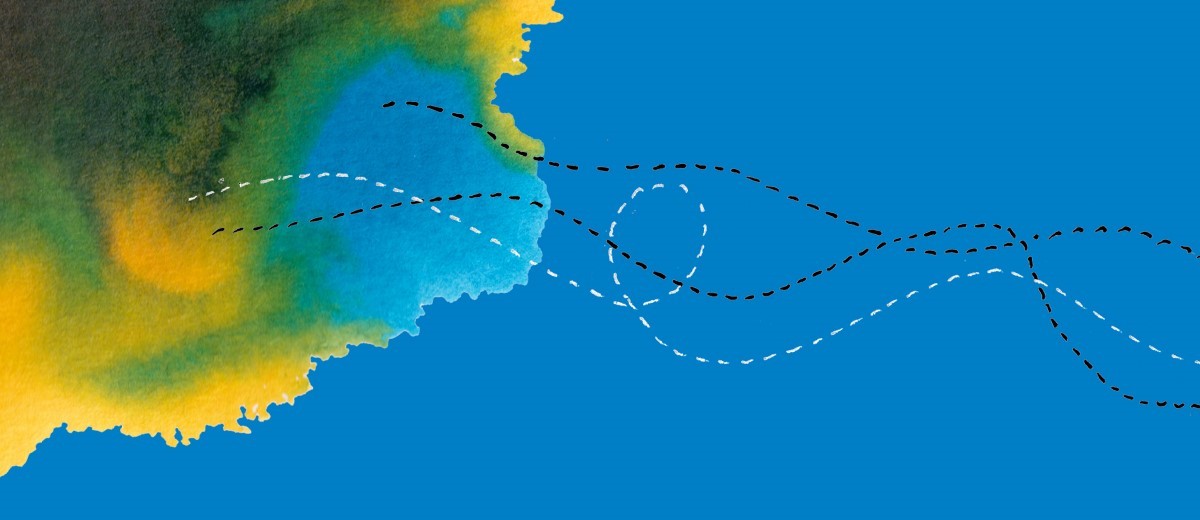

Geographic Origins

The Hellenic Republic is in south-eastern Europe. It consists of a mainland region on the southern peninsula of the Balkans, and Ionian, Mediterranean and Aegean Seas.

History of Immigration and Settlement

Georgios Tramountanas, who went by the name George North, arrived in South Australia with his brother Theodore in 1842. He was the colony’s first Greek settler. While Theodore went on to Western Australia, George, who had been born in Athens in 1822, stayed in South Australia, married, and eventually became a grazier of repute on Eyre Peninsula.

During the 1850s a small number of Greek settlers arrived in South Australia. Some were from the Ionian Islands, which were British possessions until 1864. Many others were Greek seamen who ‘jumped’ ship in order to join the rush for gold.

The first Greek to settle in the region of Port Pirie was Peter Warwick (name anglicised), who arrived in 1875. Other Greeks began arriving in Port Pirie from 1889, the year its smelters commenced operation. By 1911 there were 76 Greek South Australians.

Greek arrivals in South Australia increased in the years after the First World War. Significant numbers of single Greek men arrived from Kythrea in Cyprus, from the islands of Ithaca and Castellorizion, and from Turkey. Many of these found work at BHP’s steel production plant at Port Pirie. In 1921 there were 152 Greek South Australians.

Developments in Europe played a part in Greek migration to South Australia. In 1921 Greek forces invaded Turkey, and in the following year Greece was defeated. The 1923 Treaty of Lausanne sought to end tensions created by Turkish rule over people of Greek descent. It required more than 1,250,000 Greeks in Turkey to move to Greece and 400,000 Turks in Greece to move to Turkey. This ‘exchange of minorities’ caused a major exodus of people with some Greek refugees from Turkey migrating to South Australia. Many found work at the Broken Hill Associated Smelters in Port Pirie. Others opened small businesses or worked for themselves in market gardens.

By the mid-1920s there were approximately 500 Greeks living in Port Pirie, mainly in the western part of the town near the smelters. During this period the community consisted primarily of Greeks from the islands of Castellorizion, Levitha and Chios. In 1933 there were 740 Greek South Australians.

South Australia’s first Greek Orthodox Church, the Church of Saint George, was established at Port Pirie in 1924. The state’s first Greek community organisation, the Castellorizian Brotherhood of Port Pirie, was founded in 1925. By 1927 there were 600 Greek South Australians living in Port Pirie.

Economic depression hit BHP’s steel production industry in the late 1920s. Many of its workers were retrenched. Most of the Greeks who had worked for BHP left Port Pirie in search of work. Some of them went interstate, and a number came to Adelaide.

In the late 1920s two Greek organisations were formed in Adelaide, the Castellorizian Brotherhood and the Apollon Society. There was, however, no large body that could represent the needs of all Greeks, liaise with government departments and establish a church in Adelaide. So a meeting was held at the Panhellenion Club, 122 Hindley Street, on October 5, 1930, at which the Greek Orthodox Community of South Australia was founded. Within a year Adelaide’s first Greek school was established. In the early 1930s the community had just over 100 members. It was both a religious and cultural body.

Greek South Australians could not afford to build a church straight away. From 1930 Archimandrite Germanos Eliou held Greek Orthodox services at the hall of Holy Trinity Church near the Morphett Street Bridge. After much fundraising and hard work the Greek Orthodox Church of the Archangels Michael and Gabrielle was inaugurated in 1937. Metropolitan Timotheos Evangelinidis acted as priest and intermediary between the church and the community.

During the Second World War the Greek Orthodox Community continued to thrive. It participated in fundraising to assist the Allied forces in their fight against fascism. The community’s membership increased from 100 in 1940 to 275 in 1944. In 1944 the Hellenic Youth Club was established. After the war the Greek Ex-Serviceman’s Association and the Panhellenic Society were formed.

In 1947 there were 1,024 Greek South Australians.

There was a considerable influx of Greek migrants during the post-war period. In the aftermath of its occupation by the Axis powers from 1941 until 1945, the administration, economy and politics of Greece were in a chaotic condition. Many single men migrated to South Australia from the Peloponnese, Crete, Lesbos, Cyprus, Dodecanese, Epirus, Macedonia, and even from well-established Greek settlements in Egypt and the Middle East. They also came from European nations around Greece and from the Americas, South Africa, the Philippines, the Soviet Union and Asia Minor. Often they were sponsored by relatives already settled in South Australia. Once established, they were later joined by family groups and relatives.

In 1952 the Australian government completed an agreement with the Inter-Governmental Committee for European Migration and the Greek government. From this arrangement, selected workers and families were able to come to Australia as assisted immigrants. The Australian Council of Churches also began a migrant-aid scheme of its own. In 1953 the council made travel loans available to many Greeks who wanted to settle in Australia.

During the early 1950s the ratio of Greek males to females in Australia was 5 to 1. As a result, in the following years, young single Greek women were given special assistance to come to Australia. Some were sponsored by Greeks already settled here. Many of these young women married Greek men and established families.

At this time the Greek Orthodox Community of South Australia had a membership of approximately 3,500. The community needed a centre which could accommodate the needs of its members. After a period of fundraising the Greek Community Centre was opened in 1957. The centre is a large, multipurpose building, consisting of Olympic Hall and numerous rooms used for educational, cultural and social activities. Greek South Australians used these facilities to assist post-war refugees who were arriving in Adelaide. They helped new arrivals with language, health, legal, educational and employment problems.

During the 1950s and 1960s, many Greek arrivals in South Australia were employed on two-year contracts with the Australian government. They worked as farmers on Eyre Peninsula or in Mount Gambier, or in factories and other places where unskilled labour was sought. Greeks worked in ship building in Whyalla, fishing in Port Lincoln and as fruit pickers and growers in the citrus, stone and dried fruit industries of Renmark and Berri. Others migrated to Port Pirie and joined the substantial Greek community already there. Significant numbers established communities in Adelaide’s western area, particularly Mile End and Thebarton. During this time Greek schools and churches were established throughout South Australia and Adelaide.

In 1961 there were 9,528 Greek South Australians. By 1966 there were 14,660.

In 1975 the Dunstan government recognised the need for a liaison between the Premier’s Department and South Australian cultural groups. In that year the premier appointed two officers to be responsible for the affairs of the Italian and Greek communities. Ms Eva Koussidis was appointed as the state’s Greek Inquiry Officer. Ms Koussidis advised the government on matters relating to Greek affairs and provided the Greek community with direct access to state government.

In the mid 1970s the first official lesson in the Modern Greek language was held in a South Australian high school. By the early 1980s it had been adopted at all levels of the South Australian education system. During these years a number of homes were established for elderly Greek South Australians, and Greek welfare service organisations became widespread. At the same time Greek cultural days and celebrations were established in South Australia. They include the Glendi Festival, the Dimitria Festival, the Festival of the Epiphany and numerous other smaller celebrations.

Community Activities

Greek settlers and their descendants have maintained customs that preserve the traditions of their region of origin. Each island or area in Greece has distinct cultural traditions relating to food, music, dance, religious practices and so forth. People from Greece tend to identify themselves as first and foremost from a particular region, and then as Greek.

The most fundamental aspect of Greek national identity is the Greek Orthodox Church, which is seen as the embodiment of both religious and cultural traditions. For further information see Appendix 1, Religious Belief and Practice: Christianity. In each area of Greek settlement in South Australia the community’s first aim was to found a church. The next aim was to establish regional clubs.

Before Greek settlements could support these organisations Kafenia (coffee shops) were the main focus of cultural life for Greek South Australians. Here men could converse in Greek, play cards or Tavli, a Greek game similar to backgammon, or with koumboli, worry beads, talk about politics and business and reminisce. Initially, Greeks literate in both English and Greek read or translated letters for compatriots who had literacy or language problems. Besides coffee, a popular Kafenia drink is ouzo, an aniseed-flavoured liqueur. Meze, hors d’oeuvres, are served with drinks. These include pickled octopus; marinada, small fish, eaten whole; tahini, a sesame seed, garlic and parsley dip; and tzatziki, a cucumber and garlic dip. Tahini and tzatziki are eaten with small pieces of bread. Today Kafenia’s exist in many parts of Adelaide and throughout the state.

As soon as a Greek settlement in South Australia was large enough, a church was established as a centre of community life. Greek Orthodox churches act to preserve the Greek liturgy, culture and language and to pass on this heritage. Religious festivals and rituals to mark the major passages through life ‑ baptisms, marriages and funerals ‑ reaffirm the bonds between a congregation, its faith and culture.

Easter is the holiest festival in the Greek Orthodox calendar. For further information see Appendix 1, Religious Belief and Practice: Christianity.

On Holy Thursday Greek women prepare koulouria, pretzels; coloured eggs; offal soup; breads and cakes. Greek Orthodox Christians do not work on Good Friday. They are not permitted to eat anything containing oil; oil was used to anoint Jesus when he was taken down from the cross. At midnight on Saturday a special Mass is said to celebrate the Resurrection. This usually lasts for two to three hours. During the service the priest announces that Christ has risen from the dead. The congregation cracks coloured eggs together to signify new life. After the service family and friends break the fast by enjoying a special meal together. Later on Sunday festive lunches are eaten, including traditional lamb on a spit. Another church service is held in the afternoon.

Saints days are very important in the Greek Orthodox Church. Many Greek Orthodox Christians are named after saints. On the feast day of the saint an individual is named after, he or she attends Mass. Relatives and friends visit to wish the guest of honour well, give gifts and have a party. Name days, as they are called, are similar to birthdays. Though Greeks have adopted the celebration of birthdays in recent years, name days continue to have more significance.

Other festivals in the Greek Orthodox year include Christmas and the Blessing of the Waters in the New Year. The latter ceremony is held on Glenelg jetty. A bishop blesses the Southern Ocean and throws a cross into the water. Youths dive into the water to retrieve it. The custom originated in Greece which has always been a seafaring nation. The request for God’s blessing aims to make water safe for fishermen, sailors and swimmers.

Before an individual can have any place in the Greek Orthodox Church he or she must be baptised. Baptism marks an individual’s acceptance as a Christian. Greek Orthodox baptisms are particularly important. Unlike Catholics and Protestants, Greek Orthodox Christians are not confirmed in the church as adolescents. Baptism is both initiation and confirmation.

At the ceremony the priest cuts the child’s hair in the sign of a cross, snipping off locks at the front, back and sides of the head. The child is then completely immersed in water three times and anointed with oil. The new member of the congregation is then officially dressed for the first time and may take Communion. A huge feast is held to celebrate the baptism. Boubouniares, sugared almonds, are given to guests.

Marriage is the other major celebration in the lives of Greek Orthodox Christians. Preparations include gathering a trousseau and making the marriage bed. During the marriage service the bride and groom wear crowns and rings that are swapped three times. The priest leads the couple in a bridal dance, which takes them three times in front of the sanctuary area of the church. The repetition of these acts symbolises the binding vows that unite them as husband and wife. At a feast after the ceremony the newlyweds sit on thrones before their guests. The groom throws his garter to eligible bachelors and the bride throws her bouquet to bachelorettes. Boubouniares are also distributed among the guests.

Greek Orthodox funerals honour a person’s departure from this life. On the day of the funeral the deceased is put on display in the home of his or her next of kin so that family and friends can pay their last respects. The deceased wears a pale coloured shroud, and the mourners wear black. At the church eulogies are delivered by relatives, friends and members of clubs the deceased belonged to. At the cemetery the coffin is placed in a grave so that the head of the deceased points east. The mourners each throw a clod of earth on the coffin. The priest throws a ceramic pot or a bottle of virgin olive oil. The breakage symbolises the end of life. The mourners gather after the service to comfort each other and share a light meal. Over the next year memorial services are held for the deceased at gradually increasing intervals. At these services koliva, a boiled wheat and nut cake with the deceased’s initials written in edible silver trimmings and decorated with icing sugar, is blessed and shared. Memorial services are generally held on the anniversary of a death for five to ten years. Traditionally, women who have lost a family member continue to wear black for the rest of their lives.

While regional identity is very important to Greek South Australians, all members of the Greek community combine to celebrate Greek Cultural Month in March. Throughout the month popular singers and musicians from Greece perform in Adelaide. Often the month has a theme such as Xenitia, Greek culture and life outside of Greece, or Rembetika, Greek blues music recorded on Plaka, old 78 records. There are exhibitions of Greek arts and crafts or on the themes of Greek migration, music or literature. The month culminates in the annual Glendi Festival. Glendi commemorates Greek National Day on 25 March. On this day in 1821 Greek Nationals revolted against Turkish rule. In South Australia the festival takes place over a weekend. Greek foods such as souvalaki, meat cooked on skewers, feta cheese, olives and seafood dishes are sold. Traditional drinks like retsina, white or light red wine that has been matured in pine casks, and ouzo are available. Greek musicians and dancers perform in national costume. In previous years the Glendi Committee has organised exhibitions of icons and Greek artefacts, and performances by international artists.

Soccer is the most popular sport among Greek South Australians. In 1947 the Hellenic Youth Club formed the West Adelaide Hellas soccer team. The club was later renamed the West Adelaide Sharks and over the years has acted as a focal point of the Greek community. Presently called the West Adelaide Soccer Club it has teams in the National Premier League. The club’s colours are predominantly blue and white, reflecting the colours on the Greek flag. Greek South Australians also play for the Adelaide Olympic Football Club (formed in 1978 as the Adelaide Asteras) also in the National Premier League.

Persons of Greek birth or descent have made other contributions to South Australian cultural life. In the late 1980s Max Mastrosavas established the Theatre Oneiron, a Greek/Australian theatre company. Onerion means ‘theatre of dreams’. The company gives performances in both Greek and English.

Organisations and Media

There are numerous Greek organisations in South Australia organised on the basis of region of origin. Some of these include:

- Brotherhood of Karista SA Inc.

- Castellorizian Brotherhood of SA Inc.

- Chian Association of SA A Koraes Inc.

- Corinthian Society of SA

- Cretan Association of Australia

- Flambouron Philanthropic Society of SA Inc.

- Greeks of Egypt and Middle East Society of SA Inc.

- Imbriaki Brotherhood of SA Inc.

- Kos Society of SA Hippocrates Inc.

- Pan-Ikarian Brotherhood of Australia "Ikaros" Inc.

- Pan-Rhodian Society Colossus (SA) Inc.

Macedonian organisations affiliated with the Greek community of South Australia include:

- The Pan-Macedonian Association of S.A. Inc. This association organises the South Australian celebrations for the Festival of Saint Dimitria, the patron of Salonica in Aegean Macedonia.

- Greek Macedonian Brotherhood of S.A. Inc. Alexander the Great

- Greek Macedonian Social Club Florina

- Halkidikeon Society of SA O Aristotelis Inc.

- Kastorian Society of SA

- Western Macedonian Brotherhood of SA Pavlos Melas Inc.

Other Greek organisations include:

- Glendi Greek Festival Committee

- Greek Australian Graduates

- Greek Ex-Servicemen’s Association of S.A. Inc.

- Hellenic Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (S.A.) Inc.

- Lion’s Club of Adelaide Hellenic Inc.

- OEEGA South Australia

There are also Greek welfare, youth, childcare, elderly, student, workers’, and women’s, educational and political organisations in South Australia. Sporting and social clubs include:

- Hellenic Athletic and Soccer Club of SA Inc.

- West Adelaide Hellas

- Tavli Association of SA

Greek Orthodox Churches are located throughout metropolitan and rural areas of South Australia. All churches have Greek language and cultural schools. A primary school, Saint George College in metropolitan Mile End, was established by the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese in 1983 and is sponsored by the Orthodox community. The school teaches in both Greek and English.

South Australian Greek newspapers include:

- The Greek Tribune

- Ellinika Nea ‑ Greek News

- Teachydromos ‑ The Grecian Post

- National papers with South Australian correspondents:

- Ellenikos Kirikas ‑ Greek Herald

- Nea Patrida ‑ New Patriot

- Nea Ellada ‑ New Greece

- Neos Kosmos ‑ New World

- 5EBI-FM Radio Programs

Statistics

The 1981 census recorded 14,206 Greek South Australians.

The 1986 census recorded 13,456, and 32,304 people said that they were of Greek descent.

According to the 1991 census there were 13,629 Greek-born South Australians. 26,210 people said that their mothers were born in Greece, and 28,264 that their fathers were.

According to the 1996 census the number of Greek-born South Australians had decreased over the previous decade as a result of the ageing and death of older established migrants. There had also been some return migration as older settlers have retired. The lack of new migrants coming from Greece is illustrated by the fact that 95.7 per cent of this group have lived in Australia since before 1981. The Greek-born population for 1996 was 12,645. There were no separate figures available for the second generation.

The 2001 census recorded 11,677 Greek-born South Australians, while 38,470 people said that they were of Greek descent.

The 2006 census recorded 10,782 Greek-born South Australians, while 37,240 people said that they were of Greek descent.

The 2011 census recorded 9,756 Greek-born South Australians, while 37,677 people said that they were of Greek descent.

The 2016 census recorded 8,681 Greek-born South Australians, while 38,181 people said that they were of Greek descent.

Our deepest sympathy Stergios - we just publish Australian history articles here, but we hope you find someone in Germany better placed to help you.

God bless you.

Can you help me with the power you have?

Please call the Greeks if they can help me.

I live in Germany for three years with my family. I am an immigrant from Greece. I rented a restaurant. We are closed due to KOVID.

I have not been able to work in the restaurant since November.

I am 62 years old and I am not accepted for a job where I applied.

Where I asked for help, I did not receive anything from Greece, unfortunately because of KOVID. Here in Germany they turn their backs on us indifferently.

The restaurant owner told me to pay the rent I owe.

He told me he would go to a lawyer.

and I owe rent from the house. In a few days they will evict me. At least one rent to pay.

Both are right.

The worst thing is that I can not help my grandchildren who live in Greece and their parents do not work. There is a big health problem, and they have no help.

while the restaurant was operating I was helping.

Now I do not even have money for food.

Only a miracle will save me.

Thank you .

Bottomley, G, After the Odyssey (St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1979)

Bullock, K, ‘Australians of Greek Origin’, chapter 12 in Port Pirie, (Peacock Publications, SA, 1988)

Burton, R (ed), Odyssey: Greeks in the Riverland, Glossop High School, 1987

Drury, S, The Greeks (Melbourne: Nelson, 1978)

Janiszewski, L and Alexakis, E, Greek-Australians: In Their Own Image (Sydney: Hale & Iremonger, 1989)

Janiszewski, L and Alexakis, E, ‘Smelters, Gardeners and Caterers: The Greek Presence in Port Pirie S.A. 1890–1990’, O Kosmos, Third Annual Edition, 1990, pp36–8

Jupp, J (ed.), The Australian People: An Encyclopedia of the Nation, Its People and Their Origins, Second Edition, (Cambridge University Press, 2001)

Kostoglou, E and Kostoglou, E, ‘A Short History of the Greek Community in Adelaide’, Pamphlet for Greek Handicraft Traditions Exhibition', Migration Museum Forum, August–October 1991

Kapardis, A and Tamis, E (eds.), Afstraliotes Hellenes: Greeks in Australia (Melbourne: River Seine Press, 1988)

Papageorgopoulos, A, The Greeks in Australia (Sydney: Alpha Books, 1981)

Price, C, Greeks in Australia (Canberra: Australian National University Press,1975)

Tsounis, MP, The Story of a Community (Adelaide, 1991)

Vondra, J, The History of Greeks in Australia (Melbourne: Widescope, 1979)

Add your comment