The River Murray has been central to South Australia’s existence. Named in 1830 by Charles Sturt after Sir George Murray, British secretary of state for the colonies, the river runs 2576 kilometres from its watershed in the Australian Alps to the sea near Goolwa on the Fleurieu Peninsula, 650 kilometres of the river’s flow being within South Australia.

Indigenous peoples and Sturt’s exploration

The Murray Basin was home to numerous Aboriginal peoples, its rich environment providing food and raw materials. Aboriginal society was little disrupted other than by inter-tribal conflict and environmental reverses until 1830, when it came into contact with two elements of European civilisation – man and disease. Sturt’s exploration of the rivers he named Darling and Murray and his journal published after this trip were prime factors in promoting a British settlement in South Australia. As Sturt travelled he saw the ravages of a smallpox epidemic on the Aboriginal people. His report and smallpox changed Aboriginal life forever.

British Settlement

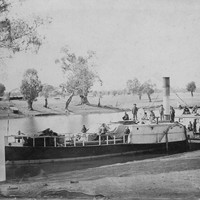

After British settlement the area near the river’s mouth was initially deemed a suitable site for a colonial capital, despite the failure of the river to connect directly with the Southern Ocean and the danger its mouth presented to navigation. Successful navigation of the river itself was achieved in 1853 through the separate efforts of William Richard Randell and Francis Cadell. Their use of steam-powered riverboats transformed the Murray into a highway for the transport of people and goods. The paddlesteamer era reached its height in the 1870s but was superseded once rail connected the river with the capital cities. However, the River Murray had value beyond a transport corridor. From the 1880s George and William Chaffey’s irrigated agricultural settlements at Renmark and Mildura (Victoria) not only changed land use but created long-term environmental problems. By the 1910s fruit growers at Renmark were aware of high salinity levels within their irrigation channels. Sub-soil salinity has increased dramatically and is now a major threat to the future viability of agriculture and horticulture.

Politically, the demand for water for irrigation purposes in the Murray–Darling Basin – from Queensland through Victoria – has set South Australia at odds with the other governments involved. From 1886 Victoria and New South Wales claimed ownership of the river and South Australians feared that massive irrigation schemes upstream would significantly lower the quality and flow of water. New South Wales’s premier, Henry Parkes, did nothing to assuage that concern when he announced that his colony owned the water and that South Australia would be in ‘breach of intercolonial obligations . . . if it [used] water to an unreasonable extent’ (Linn 1997, p.128). So critical did the Murray and its water become that the river was an important part of the Federation debate. Following a 1902 meeting at Corowa in New South Wales, a royal commission was created to ‘investigate and report on the conservation and distribution of the waters of the Murray and its tributaries for the purposes of irrigation, navigation and water supply’, but the River Murray Commission was not established until 1915.

Meanwhile closer settlement had begun – a form of settlement also used after World War I to place soldiers on the land. Without adequate training and financial support, those given small parcels of land struggled, with most irrigation settlements failing. Government attempts to conserve the waters of the Murray by installing massive storage lakes, locks and barrages to maintain river levels and flow destroyed native vegetation along the river. Huge floods, like those of 1917, 1931 and 1956, caused further damage.

Playford and the effect of the Mannum–Adelaide Water Supply Scheme

The Playford government saw another use for the Murray and in 1949 unveiled the Mannum–Adelaide Water Supply Scheme. This project bound Adelaide’s future growth to the availability and quality of river water. Another pipeline was taken from the river near Morgan to provide water to the industrial town of Whyalla on Eyre Peninsula. As water use through irrigation has increased in Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria, so the flow downstream has lessened and water quality decreased. The amount of water is finite and Adelaide’s supply is a major political issue.

During the 1960s and 1970s scientists and environmentalists began increasingly to question government attitudes towards the river. Government agreement to construct the Chowilla Dam just inside the South Australian border was challenged because of cost and the environmental catastrophe it would cause. Yet use of the Murray is a divisive issue, both in rural South Australia and Adelaide. Controversy over water flow and quality and the sustainability of the river’s ecology continues. Every issue pertaining to the river – including the diversion of water back into the Snowy River – are matters for public concern and comment.

While tourism along the Murray, with water sports and holidays increasingly popular, has become a major source of revenue for towns in the region, the environmental health of the river is one matter that South Australians can never take for granted.

Eastburn, D, The River Murray: History at a Glance: Murray-Darling Basin Heritage (Canberra, ACT: Murray-Darling Basin Commission, 1990)

Griffin, T and M McCaskill, Atlas of South Australia (Adelaide: South Australian Government Printing Division in association with Wakefield Press on behalf of the South Australia Jubilee 150 Board, 1986)

Linn, R, The River Flows: A history of Mannum on the River Murray (Blackwood, South Australia: Historical Consultants for Mid Murray Council, 1997)

Wright, M, River Murray Charts: Renmark to Yarrawonga (Burra, South Australia: BJ and MA Wright, 1987)

Add your comment