During the latter half of the 1920s, the River Torrens hosted one of Adelaide’s most popular spots for dancing and merrymaking. A large pleasure barge and floating ballroom, known as the Palais de Danse (or colloquially as the ‘Floating Palais’), was moored near Elder Park Rotunda on the south bank of the river. From its launch on 10 October 1924, the Floating Palais proved an incredibly popular element of Adelaide’s ‘Roaring 20s’ night life, but was equally beset by controversy.

Origins

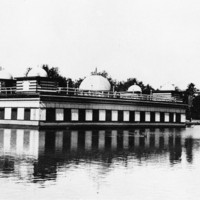

The Palais de Danse was the brainchild of Barcroft Teesdale Smith, an Adelaide-based entrepreneur who wished to create a dancing venue that operated during summer and autumn and served as a ‘healthy form of amusement’ for its patrons. Smith also sought to attract people to the river with the music, lights, refreshments and festivities the Floating Palais would provide. Originally designed to be 130 feet (39.6 metres) in length with a 30-foot (9.1-metre) beam, the vessel’s hull was constructed of ‘ordinary’ Oregon pine (Douglas fir). It featured a large dance floor with a soda fountain, a performance area for ‘one of the finest orchestras in South Australia’, and a buffet for food and drink. The design also called for it to be outfitted with electrical lighting. Its Moorish architectural motif included a roof with five painted domes and arabesque decorations. Smith wanted to significantly increase both the overall length and width of the hull, but was discouraged from doing so by Adelaide’s City Engineer. Ultimately, the Floating Palais’ dimensions, as completed, were 140 feet (42.7 metres) by 58 feet (17.7 metres). The superstructure—originally intended to be only one storey high—was increased to two storeys, and the upper level was restricted to promenading and refreshments. The vessel’s total cost was approximately £10 000.

Opening

The Palais de Danse’s launch proved inauspicious, as the water level of the River Torrens had been reduced over the previous 24 hours to allow a dredge to pass beneath the City Bridge (today’s King William Street Bridge). This left the Floating Palais high and dry in the soft mud of the river bottom. The water level was returned to its previous level in time to float the barge free for its official launch, but not before another controversy erupted regarding its design and dimensions. Misunderstanding between Smith and the City Engineer resulted in Adelaide’s City Council and Town Clerk not being informed of the addition of the second storey to the vessel’s superstructure. Upon learning of the changes, the Town Clerk threatened legal action against Smith and his business partners, and presented a list of alterations to be completed within 30 days. Failure to comply would result in cancellation of all pending licenses and permits, a court order to suspend further construction and/or modification of the barge, as well as its immediate removal from the River Torrens at the owners’ expense.

The required amendments were completed by the deadline, and the Palais de Danse opened to great fanfare on 4 December 1924. Over 1800 revellers crammed aboard the vessel, even though the City Engineer had set its maximum capacity at 700 people. Once in operation, the pleasure barge proved an extremely popular night spot, and was a celebrated feature of the annual Henley-on-Torrens rowing regatta. It was also beset by problems. On a number of occasions, the Floating Palais broke free from its moorings and had to be recovered, or was partially flooded because its moorings were too tight. As a consequence of a ‘hurricane’ that struck Adelaide on the night of 16 September 1925, the vessel once again broke its moorings, was blown ashore, and left stranded once the river’s water level receded. After consulting with Smith, City Engineer R.M. Scott agreed to close the weir’s flood gates and raise the river level by three feet (0.91 metres)—a move that successfully re-floated the hull. The Palais de Danse was undamaged, but Smith was obligated to pay the City Council approximately £25 for having the river level adjusted on his behalf.

The Floating Palais ‘Mystery’

At approximately 8:00 in the morning on Sunday, 25 November 1928, the Palais de Danse rapidly began taking on water and settled onto the bottom of the River Torrens a short distance from Elder Park Rotunda. The vessel’s caretaker, Louis Bovet, awoke suddenly to a series of ‘explosions’ that sounded like the ‘beating of a muffled drum’ and shook the hull from stem to stern. Within an hour, more than a foot (0.3 metres) of water covered the dance floor and the hull was stuck fast in the mud.

Bovet later claimed that during the very early morning of 25 November he observed a small boat partially hidden behind reeds near the Floating Palais, as well as what he thought were two cigarette embers burning on the bank opposite. Later the same day, a woman in Mile End reported to police that a group of ‘half a dozen young men dressed in khaki’ visited her home early that morning, became abusive, broke windows and a door lock, and left behind a large milk can later identified as property of the Floating Palais. The milk can had apparently been last used on the night of 24 November and was only reported missing after the barge sank. On 26 November, City Council gardeners discovered a cache of approximately 60 unused .303 calibre rifle cartridges among shrubs on the northern riverbank opposite the barge. Taken together, these occurrences fuelled speculation that the pleasure barge’s sinking was the result of a deliberate act.

Subsequent police investigations were ultimately inconclusive. While the Palais de Danse’s new proprietor, J.L. Herbert, maintained the incident resulted from either a small bomb or bullets fired from shore, other possibilities emerged. For example, one police officer theorised that gas fumes from cooking appliances could have built up within the vessel and generated an explosion. The most likely theory, however, is that the barge’s timbers below the waterline were affected by wet rot to such an extent that one or more of them catastrophically gave way.

Final Days

The Palais de Danse was re-floated by the end of November 1928 and participated in Henley-on-Torrens celebrations the following month. Subsequent inspection of the barge beneath the waterline revealed most timbers had been weakened by rot and were no longer structurally sound. The Floating Palais’ doors closed shortly thereafter and by February of the following year plans were in motion to sell and dismantle the hull. Timber merchant S.R. Dickinson purchased the vessel for £500 in April 1929 and moved it to the northern bank of the River Torrens near the Morphett Street Bridge, where it was demolished. Two months later, 50 000 feet (15 240 metres) of timber extracted from the Floating Palais, as well as iron plating, metal piping, and three of the five Moorish domes that once decorated its roof, were sold by J.A. Sando & Son at the site where the hull was broken up.

What fantastic memories Jennifer, thanks for sharing your mum's story.

My mother remembers going to the Palais with her mother as a five or six year-old. Her Uncle Jim was some sort of spruiker for the Palais. She has fond memories of it, and loved going there. She remembers its ultimate demise. Her contacts with the River Torrens continued. She took part in a Food for Britain flotilla after WWll. In 1948 she married Arthur Brooke whose firm SA Brass manufactured the original brass fountain that was in the Torrens lake for many years.

[Adelaide] Chronicle, 16 May 1929, ‘The Floating Palais: Demolishing the structure’, p. 58.

[Adelaide] News, 24 December 1924, ‘Floating Palais’, p. 2.

[Adelaide] News, 26 November 1928, ‘Sinking of Palais: Rifle cartridges found, foul play suspected’, p. 1.

Summerling, Patricia, The Adelaide Parklands: A social history (Adelaide: Wakefield Press, 2011).

The Advertiser, 26 November 1928, ‘The Floating Palais damaged: Was it a bomb?’, p. 10.

The Advertiser, 27 November 1928, ‘Floating Palais mystery: Cause of accident still unknown’, p. 14.

The Mail, 26 September 1925, ‘On again, off Again: Floating Palais floats’, p. 1.

The Register News-Pictorial, 7 February 1929, ‘Floating Palais ends career: Wet rot bad in timbers of the pontoon’, p. 7.

The Register News-Pictorial, 30 April 1929, ‘Floating Palais has gone: Will be dismantled for timber’, p. 8.

The Register News-Pictorial, 11 June 1929, ‘Advertisement of sale, J.A. Sando & Son’, p. 31.

Add your comment