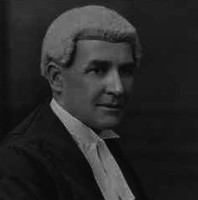

Thomas John Mellis Napier was born at Dunbar, Scotland, on 24th October 1882, the son of medical practitioner Alexander Disney Leith Napier and his wife Jessie (née Mellis). When he was five the family moved to London, where he was educated at the City of London School. In 1896 his father accepted an appointment as Senior Resident Physician at the Adelaide Hospital, despite a ‘black ban’ by the British Medical Association arising from the ‘Hospital Row’, a bitter dispute between the medical staff and the government of Charles Kingston. Young Mellis stayed behind to complete his schooling and was reunited with the family in 1898. In Adelaide he found his father socially ostracized and only Kingston willing to train Napier for his chosen profession, the law. He studied at the University of Adelaide and was admitted to the Bar in 1903. He helped to revive the moribund Law Society, lectured at the Law School, drafted several long-lasting statutes and took silk in 1921.

Napier’s conduct of important government business was rewarded with appointment as a Supreme Court judge in 1924. He became known for the erudition he displayed in Equity and testamentary cases and for his view that the law should be a servant of the people. Prime Minister Lyons appointed him Chairman of the Royal Commission into Banking (1935-7) which influenced regulatory policy for two decades. In 1942 Napier was made Chief Justice of South Australia and was duly knighted the following year. In 1945 he was appointed K.C.M.G.

Napier’s chief justiceship was notable for three reasons. First, his open, friendly manner among his judicial colleagues ensured he was not overruled on appeal for two decades. Senior counsel, however, went over his head to the High Court and Privy Council, and from about 1960 new colleagues saw things differently. Secondly, Napier pursued the Chief Justice’s traditional extra-judicial roles, taking himself very seriously in each. As Lieutenant-Governor of South Australia from 1942 to 1973, he was Acting Governor for a longer aggregate than any governor’s term of office, making a point of moving into Government House even for a matter of a few days and parading in cocked hat at every opportunity. He served as Grand Master of the Freemasons, President of the St. John Council and Chancellor of the University of Adelaide (1948-61).

The third noteworthy aspect of his term was the Rupert Max Stuart case of 1958-59. Stuart, an Aboriginal with little English, was convicted of the rape of a young girl and sentenced to death. The trial judge was backed up by the Full Court (Napier presiding), the High Court and the Privy Council, as well as the Premier, Thomas Playford, who declined to commute the death sentence to life imprisonment --- all despite strong allegations of serious police brutality and mounting objections to capital punishment. In 1959 Napier displayed a serious lack of judgement in accepting the chairmanship of a Royal Commission into the affair. The Commission’s predictable finding against a new trial forced the Premier to defuse the situation by commuting the death sentence against Stuart.

The Stuart case was Napier’s nadir. His Banking Commission recommendations were already being overturned and his judicial colleagues were no longer reticent about overruling him. He retired from the bench in 1967. For fifty years he had borne the cross of his father’s strike-breaking. Even in 1952 medical men lobbied (unsuccessfully) against his election as President of the Adelaide Club because he was the son of ‘that dreadful Dr. Napier!’.

Sir Mellis Napier died on 22nd March 1976. He was given a State funeral and was cremated. The Napier Building at the University of Adelaide was named after him and a bust by John Dowie is situated in the Prince Henry Gardens on North Terrace.

Chamberlain, R., The Stuart affair (Adelaide: Rigby, 1973).

Giblin, L.F., The growth of a central bank: The development of the Commonwealth Bank of Australia 1924-1945 (Melbourne: University Press, 1951).

Inglis, K.S., The Stuart case (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1961).

Add your comment